I read a book a few weeks ago that has turned my head! As I dived into each chapter, I learned more and more frightening statistics that expose the reality of the so-called ‘energy transition’. More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy by Jean-Baptiste Fressoz (2024) is an eye-opening text that considers the climate emergency while arguing that in reality – across the globe – more critical energy resources are being used than ever before./

Fressoz cites the ‘seductive marketing’ of the 1970s and onwards as a factor that persuaded populations that we are experiencing an ‘energy transition’ while glossing over the reality, ie, the rise in energy sources necessary to produce what is needed to ‘go green’ (in other words, just what is needed to create our solar panels, wind turbines and batteries).

Global trade and population growth has required greater use of all energy sources, with food production a useful example. Take tomatoes. Studies show how commercial greenhouse production methods in the tomato industry increase their yield by as much as 80 percent by using increased levels of CO2 . More tomatoes – more CO2 – winners and losers, then?

Consider data centres, the places that do all the work every time you tap in a question to your favourite search engine and get an answer in a fraction of a second. Every data centre uses as much electricity and water as a small town! In the UK, energy usage for data centres has risen by 400 percent in the last ten years, with continuing increases likely as a result of AI. Currently, they use about 2% of energy worldwide and one report suggests, ‘The situation is more acute in Ireland where, by 2026, data centres could account for 32 percent of all power consumption due to a high number of new builds planned.’

Frightening, eh?!

Another example, says Fressoz, is plastic:

‘Plastic is responsible for three to five percent of global emissions and whose growth seems unstoppable. Production has quadrupled since 1990 and vast markets remain to be conquered. On average, an American consumes four times more plastic than a Chinese person, and 15 times more than an Indian. The carbon intensity of plastics has increased over the last few decades as more of them are produced in Asia from coal. The problem is that substitute materials – paper and, especially, aluminium – have an even higher carbon footprint. Whatever happens to the internal combustion engine, plastics will continue to ensure decades of profits for the oil industry.’

Our everyday world has become more complex, leaving the hope for simple ‘recycling’ more of a pipe dream:

‘For example, a tyre in 2020 contained as many different elements as a whole car a century earlier. A telephone in the 1920s contained twenty different materials; a century later, a smartphone uses sixty of the eighty-seven metals in the periodic table of elements.’

Fressoz provides plenty of data I found chilling. Take, for example, the mechanism known as BECCS – bioenergy combining the capture and storage of CO2. Fressoz explains:

‘To avoid exceeding 2°C by 2100, this industry, which is still non-existent, would have to pump from the atmosphere and bury underground between 170 and 900 gigatonnes of CO2 by 2100 – absolutely gigantic quantities, equivalent to or even greater than the world’s wood production. To have an effect, this undertaking would have to be scaled up to staggering proportions, with some scenarios forecasting a forest plantation area dedicated to BECCS of 1.2 billion hectares, or more than three times the surface of India.’

The idea of ‘green washing’ is a familiar one, the idea that renaming something will somehow persuade people to think differently about it – ie, the suggestion that ‘green growth’, must somehow be better.

We might consider the idea of an electric car as a positive addition to our challenge to limit climate change – until we are reminded by Fressoz that:

Half of the world’s EVs are in China, where two-thirds of electricity is produced from coal. Orwell’s comment is as true today as it was in 1937: coal and miners have never powered so many cars.

Our world is so interconnected that it seems increasingly impossible to do what we need to do to halt the advancement of environmental disaster.

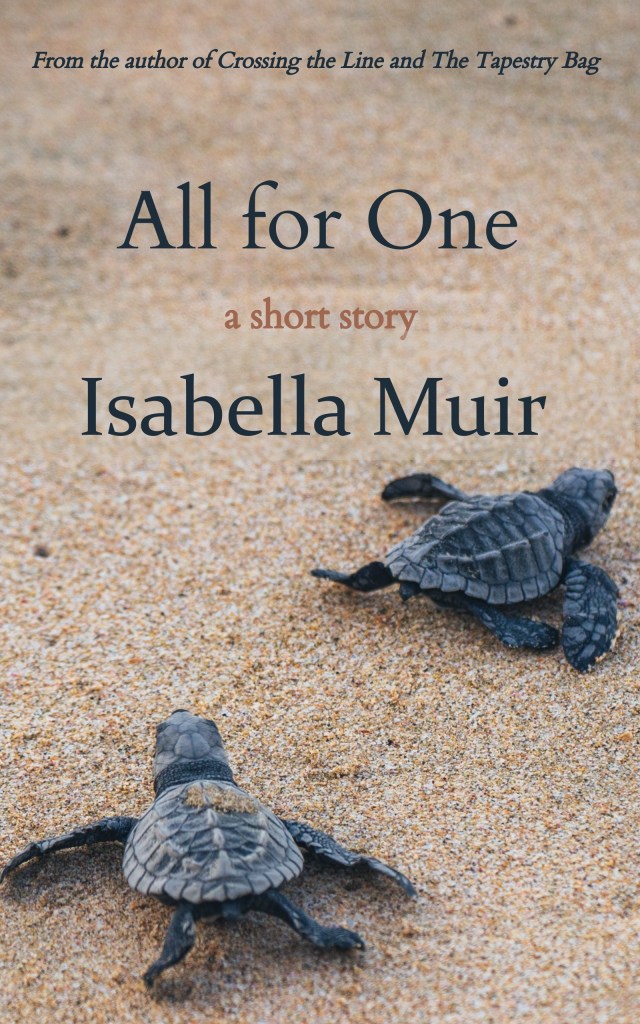

While writing this blog post, I have been trying to think about an upbeat ending, to help readers go away with a smile, instead of a frown. In the end I was drawn to a short story that encompasses the importance of looking out for each other – told through the eyes of a child. Click on the image below to enjoy All for One for free!

Happy reading!

My next post – Why history? – explores why historians investigate the past. Spoiler alert – the reasons are as varied as the historians themselves!

Just click on ‘subscribe’ on the home page to follow my website, to ensure you don’t miss out on forthcoming articles.

To continuing exploring the topic of climate change and the ‘energy transition’ I can highly recommend More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy by Jean-Baptiste Fressoz (2024).

Leave a Reply